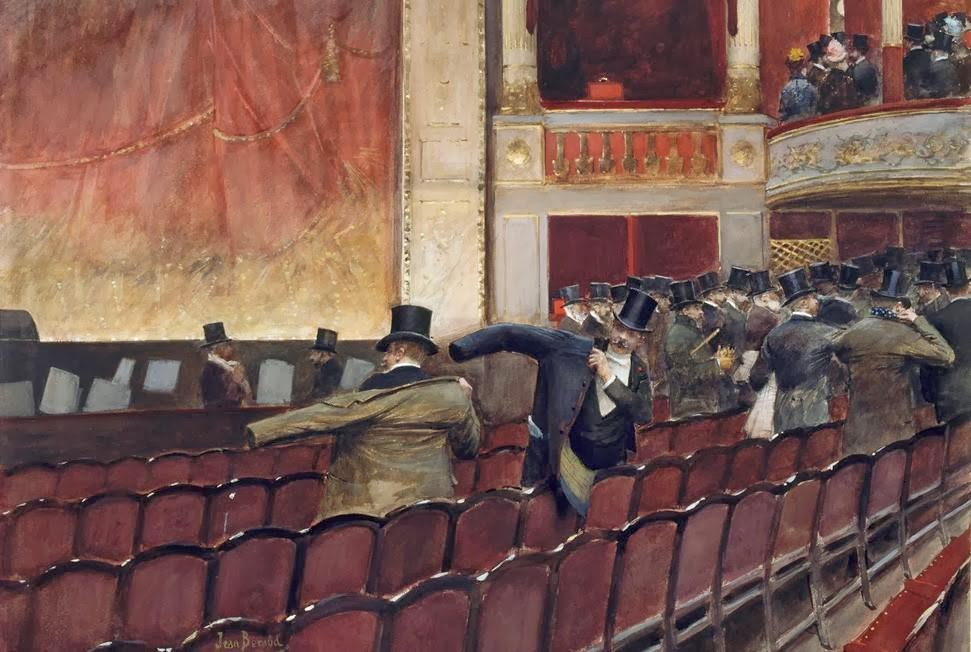

Jean Béraud, La sortie de théâtre, 1900

•

The listening predominance

An opera is made to be seen. A symphony or a string quartet is to be listened to.

This truism has not always been universally accepted. In 1922, George Bernard Shaw, probably as a reaction to some wretched staging, stated that the best way to go to opera was to sit at the back of a box, put your feet up on a chair and close your eyes. «If your imagination can’t do at least as well as any scene painter, you should not go to opera». Many of us who are content with listening to our records at home will agree with the acerbic Irish writer. But the affirmation can also be turned around. As Patrice Chéreau once stated, «If the stage director isn’t capable of doing better than the imagination of the spectators, he’s useless».

For a long time, operatic stage directors didn’t even exist, the directions were all in the score. Production designers painted the backdrops, but the staging was all in the hands of the singers, who also chose their costumes.

Starting with Wagner, the composer began to dictate law, even down to the smallest detail, and the staging of Wagner’s works coincides with the history of operatic staging tout court. The papier-mâché and painted canvases of the nineteenth century made way for the abstract and three-dimensional sets of Adolphe Appia in the early 1900s, the symbolic poetry of Wieland Wagner in the ’50s and ’60s, Chéreau’s revolution in 1976, and the controversial present-day reinterpretations.

The issue is always the same: tradition or innovation? In Italy, above all, “the cradle of opera,” what will happen «if the Italian theaters do not change their attitude, if they don’t understand that it’s self-destructive to reject a true confrontation with modernity, if they don’t start commissioning new works from today’s composers once again, if they don’t stop hiding behind the pretext of the ‘audience’s-favorite-repertoire’ which conceals only their fear of daring and of defending their choices. A look at the playbills of our lyric foundations reveals the distressing obviousness of the programming, the prevalence of the foreseeable». This is Sandro Cappelletto’s bitter conclusion in the Italian newspaper La Stampa on January 31, 2013.

⸫

The demand for opera has changed a lot: until a few decades ago people went to the opera knowing they were going to listen to an orchestra conducted by a particular conductor and sung by varyingly competent singers who were varyingly famous. Ah yes, there would be varyingly attractive sets (daring perspectives, bold reconstructions, charming lights) and varyingly “rich” costumes. And the stage director? Well, he would tell the singers where to stand and how to move. Traffic control, almost nothing else.

There have been exceptions like Luchino Visconti (who was from the movie industry) or Strehler (from the theater), who freed the opera of the second half of 20th century from its 19th-century legacies (painted canvas, papier-mâché, warehouse equipment, conventional environments), while others (Pizzi, Zeffirelli and, in his own way, Ronconi) brought opera back to the grand dimensions of its exterior magnificence, but rendered it partly elitist and impervious to the demands of contemporariness. In the words of Daniele Abbado: «It is no longer possible to deal with a work of musical theater like an object of the past: this falsely uncritical position aims to keep an idea of ‘tradition’ that is at most consolatory. This idea is usually accompanied by the need to express, onstage, sensations of glitz, a wealth of images and materials, often revealing impotence in the narration and the interpretation, which is the same thing».

⸫

Ever since Patrice Chéreau and his “infamous” rereading of Wagner’s Ring for its centenary (Bayreuth, 1976), the stage direction of opera has never been the same. All the way to today’s much reviled Regietheater (defined Eurotrash overseas), where sometimes one suspects that the stage director has a kind of oedipal animosity towards both the composer and the librettist. But even here it is necessary to distinguish between mock and forced innovations and the search for new connections between music, drama, entertainment and contemporary issues. The same thing happened in prose theater: who would accept a Shakespeare play performed the way they did it sixty years ago? Not to mention ballet: the Nutcracker by Mark Morris, Giselle by Mats Ek or Swan Lake by Matthew Bourne (to quote three examples at random) are choreographies that, even without the tutus and pointe dancers, attract masses of theatergoers.

In fact, the opera audience is changing. The old core formed by traditional subscribers is disappearing due to natural causes, but globally a new audience has increased in number, and a lot; this audience enjoys performances through media provided by contemporary technology (television, cinema, internet, digital recordings).

Starting in the late 19th century, music was no longer played on the piano in the living room but came from music-making boxes: first, the radio and then the phonograph. For over eighty years, we studied to, we raved at, and we have been thrilled by the sounds that magically sprang from those grooves.

Until a few decades ago, we only listened to records at home. There were a few meager television broadcasts, but the enjoyment of opera was almost exclusively audio. For the vast majority of music lovers, Callas, Corelli, Sutherland and Del Monaco were a photograph on the cover of a vinyl record. The drama was all and only in the voice.

One could even say that for a long time the enjoyment of opera was distorted by the limitations of technology. As if art scholars only had black and white pictures at their disposal for a long time and later discovered the real colors of the paintings!

First there were the awful video recordings on VHS, followed by DVDs and blu-rays, and then live broadcasts in high definition. And the audience that can now “attend” a performance – see it, not just hear it – has greatly increased. A production at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, for example, has an average of a dozen performances that are almost always sold out. This means that about 40 thousand spectators will attend each live production.

But the same performance is broadcast in thousands of cinemas scattered throughout the United States and worldwide; it can be seen on dedicated television channels and is sold on DVD. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the actual number of viewers is more than tenfold. And it is not always a specialist audience, they’re often a young crowd and accustomed to non-traditional and elaborate shows. The new technologies have radically changed our way of viewing: close-ups of singers, instrumentalists or details of the sets, the use of microphones and amplifiers (is it still important today for a singer to have a powerful voice?), the use of video or computer graphics – these are all instruments for renewing an art form that perhaps will survive, or at least «prolong its death throes for another 50 years», according to Luca Ronconi’s famous quip.

⸫

At the end I want to quote the American artist Alfred Eaker: «These puritan opera attitudes are predominant here in the west. It is because of them that opera companies, catering to the ultra conservatives (who feel as if they own the art form) are forced to stage a La Boheme every single season, simply to keep themselves out of the red. Meanwhile, Europe, which has long staged opera in contemporary settings, has a thriving opera scene. Do the math. The supposed opera fans have killed the art form they claim to love. They have killed it by putting that art form on a pedestal, edifying it, dehumanizing it, and keeping it stale. At the sign of even a single 21st century dress on a singer, these fans will be as sounding brass, wailing blasphemy behind the curtain. It is no wonder opera is in its death throes here in the States? What potential music lover, under the age of thirty, would want to even explore an art form held captive by such a constipated lot?».

⸫

This blog has been evolving over time: besides the main portion featuring tabs on the DVDs on the market, I have added a section with the reviews of the performances I have attended since I started this blog, and one with descriptive files of the outstanding buildings that host this ephemeral art form. Recently more sections have been added including occasional concert, theater and books reviews .

Renato Verga, 21 May 2014

᛫

⸪